|

In the vast and dynamic world of baseball, where the crack of the bat and the cheers of the crowd echo through the air, hitting transcends mere physical prowess. It is an art, a delicate dance between what the eyes perceive and the body executes. At the heart of this mastery lies a concept often overlooked—A Personal Vision Plan.

The Visual Symphony of Hitting Hitting, fundamentally, is a visual task that seamlessly intertwines with the physical aspects of the game. Imagine a symphony where the conductor is the player's vision, guiding every nuanced movement from the initiation of the swing to the final connection with the ball. The depth of visual focus during this symphony dictates the player's ability to execute a quality swing, making it, perhaps, the most challenging visual-motor task in all of sports. Crafting the Personal Vision Plan Our hitter's philosophy revolves around the core principle of enhancing his ability to square the ball effectively. This quest involves a meticulous Personal Vision Plan—a roadmap designed to elevate his visual acuity and, consequently, his hitting prowess. The plan commences with visual preparation, emphasizing the importance of seeing the ball as early as possible. It is not merely about tracking the ball's trajectory but also discerning the spin, allowing the hitter to predict where the pitch will land. This foresight is the key to squaring as many hittable pitches as possible while adeptly recognizing those that are best left untouched. The Mindset of Timing Taking a pitch is not a passive act but a strategic pause. It's about gaining the confidence that one is on time and ready for whatever the pitcher throws. Every successful hitter understands the significance of timing and how it intertwines with the visual aspects of the game. "Follow my eyes as they lead my body," our hitter believes, highlighting the indispensable connection between perception and execution. Seeing is Believing In the realm of hitting, seeing is believing. Trust in one's vision becomes the linchpin of success. The eyes become the guide, providing cues and insights that lead to split-second decisions. Success, according to our hitter, is a result of developing the trust to "follow my eyes," an unwavering belief that his vision will lead his body to success. "I see what I look for," he asserts. The importance of actively seeking the right pitch cannot be overstated. In the blink of an eye, decisions to swing or not swing unfold within 0.20 seconds of the pitch revealing itself. This fraction of time encapsulates the essence of hitting—swift, calculated, and driven by a well-honed vision. Strategic Planning for Success Every pitch, every at-bat, demands strategic planning. The hitter must consider the unique conditions of the game moment—pitcher tendencies, game situation, and personal strengths and weaknesses. Success lies not just in reacting but in having a vision plan that is practiced and ingrained in routine. It becomes a subconscious guide, a reliable ally in the heat of the game. Conclusion: The Visionary in the Batter's Box In the intricate world of hitting, where split-second decisions define success, our hitter stands as a visionary in the batter's box. His Personal Vision Plan is not just a strategy; it's an art form—a symphony of visual acuity, trust, and calculated decisions. Aspiring hitters can draw inspiration from this approach, understanding that the path to greatness is paved by a keen eye, a well-crafted plan, and unwavering trust in their own vision. The art of hitting, after all, begins with what you see and ends with what you see.

0 Comments

VISUAL INSIGHTS is an open conversation about Sports Vision and Performance with host Ryan Harrison and special guest. Guest include former players, current players, coaches and industry leaders from various sports and clinical backgrounds.

AuthorRyan has been training visual performance skills with athletes for the last 20 years. As co-creator of SlowTheGameDown, Ryan has learned his craft alongside his father Dr. Bill Harrison. Dr. Bill was a pioneer in the field of Sports Vision. Ryan has worked with over 13 MLB teams, numerous College Softball and Baseball teams. He has also worked with professional and amateur athletes in all sports from Golf, Hockey, Volleyball, Tennis, MotorRacing and more. Ryan currently runs the NDVPerformance Training Center in Irvine, Ca and Serves as the Director of Training for NeuroDynamicVision.

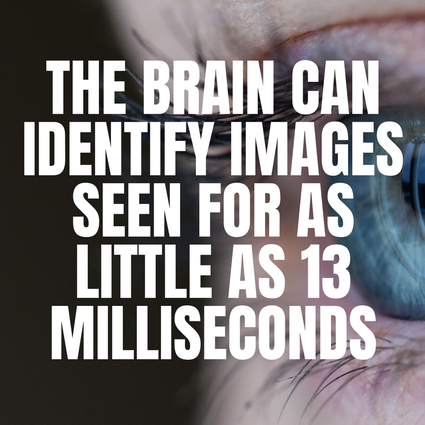

A team of neuroscientists from MIT has found that the human brain can process entire images that the eye sees for as little as 13 milliseconds — the first evidence of such rapid processing speed. (Source) . What limits us from recognizing faster? Technology. This research was limited by the speed of the monitor used. Maybe we can recognize faster. What matters in sport is we give our self the opportunity to recognize as much as possible and as quick as possible with accuracy and intent. What we do know is what limits this ability. Fatigue, nutrition, visual accuracy, focus injury and more. So if we can prepare our vision for success it gives us the optimal ability to see as little as 13 milliseconds and maybe quicker. Ryan HarrisonSports Vision Specialist Text Validated by Ezvid Wiki Editorial on 20 March 2020 Repost from https://wiki.ezvid.com/m/6-ideas-for-athletes-who-want-to-improve-performance-CNy4UhWlSC9QA Anyone who's ever trained for a marathon, scaled a rock wall, or just gone for an extra-long bike ride knows the feeling of hitting the wall. Professional athletes have long sought ways to get a competitive edge and push their limits, but thanks to technology, everyone now has access to these tools. We're featuring several options for those serious about utilizing the information at their disposal to develop a plan and break down those barriers. This video was made with Ezvid Wikimaker. Resources For Reaching Your Athletic PotentialNameDescriptionDiamond KineticsMotion technology company employing analytics to enhance baseball and softball player development

Halo NeuroscienceNeurotechnology brand that helps players develop faster muscle memory with the Halo Sport, which supplies a small electric current to the area of the brain that controls movement, putting it into a state of hyperlearning SlowTheGameDownTrains athletes with development programs focused on areas like rehabilitation and visual performance TD Athletes EdgeStrength & Conditioning facility focused on performance-based training, nutrition, and recovery for athletes of all levels InsideTrackerProvides personalized, evidence-based solutions for nutrition and exercise based on blood test results Dr. Greg WellsAuthor of Superbodies and The Ripple Effect, and host of a popular weekly podcast BRIAN CAIN PODCAST TRANSCRIPTION

briancain.com/blog/bc90-ryan-harrison-slow-the-game-down-vision-performance-trainer.html Cain: Hey, how are you doing? This is Brian Cain, your Peak Performance Coach with the Brian Cain Peak Performance Podcast. Today our guest is Ryan Harrison. He is one of the top vision performance coaches in the world. He works with many Major League Baseball organizations, top college baseball and softball programs, a list of hockey players and hockey programs, football, MMA, tennis. You name it – he has worked with them on vision performance training. One of, if not the best, and most highly regarded vision trainers in the world. Ryan Harrison, www.SlowTheGameDown.com, I appreciate you joining us today, man. If you would, would you please give our listeners your background into how you got started in vision performance training? Harrison: Thanks, Brian. That is a good question. I have been doing this for about 16 years now and the company has been doing it for about 40-some odd years. My degree is in exercise physiology. My father, Dr. Bill Harrison, has been doing this since 1971 with the Kansas City Royals and the Royals Baseball Academy. I’d say about 16 years ago he asked me to go help him work with some teams. At the time we were working with the Cincinnati Reds, Kansas City Royals, Atlanta Braves. I went out there and, like any son, you never listen to your dad. You have all this great advice and at the same time you never listen to him. Now being older, I went out with him, watched how the players received this information, watched how he went about things, and realized, “Hey, Dad, you have something that is going on here. These players are responding to the way you teach them, the way you talk to them, the way you show them how to use their eyes.” So, taking my background in exercise physiology, we kind of developed a better, broader plan where we can get out to the masses a lot more. Trying to help players understand how to see the ball, what they see, what they don’t see. Having training products where they can develop visual skills so that their visual skills are at a high level in things that we test in the big leagues. These players are all able to get to that level. So, again, I have been doing it for 16 years. This last season we worked with the Toronto Blue Jays and the San Francisco Giants. I worked for many different organizations in different capacities and worked with a lot of different college programs and a lot of individual athletes that come out to us (whether they are hockey players, whether they are football players, whether they are baseball players, golfers) and looking at the game a little differently than what most people do. We look at it from a visual perspective. How can we enhance their visual perspective of the game? You know, Brian, when athletes are at their best, they see things, things slow down, they don’t think about a lot. When they struggle, they think about a lot. The ball looks fast. The ball looks like a little missile. What we want to do is learn how to control that and teach them a method of how they can slow the ball down or slow the action down and be in the right visual focus. Cain: I have worked with some of the same programs that you have here at Florida State with their softball program, at LSU, and one of the things that I hear their coaches say (and I’ve heard you say here now working this camp with you for the last 4-5 years) is, “You can’t see and think at the same time.” Is that right? Harrison: Yeah. When you think, you can’t see. Cain: Explain that a little bit more. I think it’s marvelous. Harrison: Well, I’ll give you a great example. We all had this back in school. You’re reading a book or reading the newspaper and flipping a few pages; you get there and you go, “What the heck did I just read?” Cain: It happened today. Harrison: Now if we took some video analysis and analyzed how your eyes functioned and moved, they moved beautifully but you were lost in thought about something else and you weren’t taking in that visual information. That happens to us driving. It happens to us playing sports. It happens to us in life. It’s learning how to control that and being able to (what I call) inhale the visual information at the right time. Hitters sometimes are thinking so much about the umpire. They are thinking about what their coach thinks. They are thinking about who is in the stands. They are thinking about what their parents are doing. They get away from the task at hand, which is learning to see the ball and slow the ball down and focus on the targets. Cain: A couple of the things I’ve seen you guys do here at the camp is you’ll have the vision rings (a white ring with different colored balls on it), and they’ve got toss and catch, and you’ve also got the ping-pong ball shooter where they’ve got to catch and call different balls. What are some drills that when you go in to work with the team – and for the coaches that are listening to this podcast, if you have never invested in vision training, what I love about www.SlowTheGameDown.com, or what Ryan does is he comes in and leaves you with a program that you can do year round. What are some of those techniques or training strategies that you use with teams? Harrison: That is a good question, Brian. Here is the deal: Everyone always wants to know what is the one quick fix. There really is not one quick fix. Especially when it comes to vision, there is a variety of players; they’ve all perceived visual information differently. Coaches want them to understand what they’re seeing. Most of them don’t see the way we think they see. I was trying to break it down as two things. There is hardware and there is software. What vision hardware is is more of the visual clarity; it’s more about depth perception; it’s more about visual recognition, visual processing skills, more of the hardware of the eyes and the brain and how they work together. On the other side of it is the software, which is more about how to use your eyes, how to look in the right spot, how to control your focus, how to make the ball look bigger from your eyes. Some of the training that we do (there are a variety of different tools) have to do with enhancing the hardware, so we have to enhance the software. You brought up the rings. The rings have to do a lot about controlling your focus and learning how to control your eyes to look at the right thing. One thing that people don’t understand is the brain is very powerful to what we see. We actually really only have clear central focus on about a five-degree cone and all the other is more of our peripheral vision. We see in our peripheral vision but it’s not as crisp, it’s not as clear, it’s not as accurate. Our brain wants to put that information together. When they are using their ring, they want to learn how to slow it down, they want to learn how to fine-tune their focus on the right stuff. It’s the same thing with the ping-pong ball machine. Vision is not just about seeing. It’s about how they process the information and how they react to it. One of the things that I see a lot in a lot of drills that are done is they see, then they think, they talk, and then they try to put a reaction to it. Sport is more about see and react and putting those programs together. So with the ping-pong ball machine they are seeing and they are making a reaction based off what they see. We do that with a couple others. Our VPX trainer poster is a great program with on-scene react where we add a lot of fatigue and a lot of movement and getting the control of the eyes as well. Cain: I know you guys just came out with a book and I know it’s out there on the table. I was flipping through it earlier. I haven’t had a chance to read it yet. Tell me about the book and what are some of the advantages or things that coaches or athletes would learn that are listening to this? Why would they want to get the book and where can they get the book? Harrison: Well, it’s funny. Sixteen years ago when I started working with my dad, I said, “Hey, you’ve got to get a book out,” and sixteen years later he finally got his first book. We finally made it to publish. Even though we have the first one out, we have two more that are about to roll out as well. The first one has to do with how to perform like the pros. It’s very interesting. It’s a little bit different than most books in the fact of it’s not an instructional manual. It’s not a tell-all book. It’s a story of his career back from the 70s and how he presented ideas to the guys back in those days. George Brett. Things that went to Charley Lau. A lot of people know about Charley Lau as a hitting coach. Things they presented to the San Francisco Giants. Just over time periods telling stories of how players take that information and how they’ve learned how to get visual and focus on there. The two other books that will be coming out will be one more specific to hitting and the other one will be more specific to pitching, on how to focus and how to perform from a visual perspective on doing that. So they can get that book at our website at www.SlowTheGameDown.com. It is on Amazon as well. Being the first book, we just rolled it out and launched it. Cain: Love it. Harrison: Some good stories. Cain: Yeah, I can only imagine, man. Just knowing the little bit about your father that I do, he is one of the pioneers of the mental game really. If you look at the mental game or vision training and that side of performance, he is probably the first guy who really got into professional sports. Very similar to Ken Ravizza. That is where I first heard of your father, when I started with Ken Ravizza at Cal State Fullerton. I know you’ve met Ken and known Ken for many years. If we can kind of transition maybe a little bit into what is the mental game? I think sometimes there are people that try to combine the two. I see them as both necessary but separate trainings. What is your take on the mental game? Harrison: Well, that is a good thing. Ken actually sat in on some presentations back in the early 70s with Cal State Fullerton. We are very separate on what Ken does, what you do, what we do, and they all kind of work together. The question I tend to ask a lot of players (and you ask the same question – we ask a little differently) is what percentage of the game is physical? You’ll have some players who have heard 10%, 20%. Your number is all over the place. What percent of the game is mental? Oh, 90%. The third question I ask is what percentage of the game is visual? They all get stunned. My bias is it’s 100%, 100%, and 100%. They are all important parts to this game and they all work together, they all cross over, but you need all three to be that excellent athlete. That is what these top players have; they have a great visual plan, they have a great mental plan, and they have a great physical plan. If they can combine the two [three] – from my perspective, the eyes lead the body. You could have a great swing. You could have the prettiest swing in the world, but if you don’t see it accurately, it doesn’t matter. You could have the great mindset that you can run through a wall, but you still have to have some physical skills to be able to hit the ball or catch the ball or throw the ball. You also have to be able to see it at the same time. You could have the greatest eyes in the world, but if you’re thinking too much and not allowing your eyes to work and you’re not confident and you don’t have the physical skills, it doesn’t matter how good your eyes are. You could have great eyes and nothing else. So it’s a combination of all three working together. I think to me, if they can get the visual first, it helps the mental side and it helps the physical side quite a bit. Cain: I had a chance here last year (I think it was at Florida State Camp) to see you work with some of the athletes. One of the drills you did was you would have them stand like they were a shortstop and you’d roll them a ball and say, “I want you to look at the ball.” You’d roll one to them and say, “I want you to look at the bottom of the ball.” I was over there and I jumped in and had an athlete roll the ball to me. I looked at the top, looked at the bottom of the ball, and it was amazing how much lower I was able to stay on the ball when I was looking at the bottom of it. As a high school baseball player and infielder, I remember I could never stay down on a ball. They’d always say, “Oh you’re scared of the ball.” It’s like, well, no. I didn’t care if I got hit by the ball. It was just for some reason I couldn’t come down. Maybe it had something to do with where I was looking on the ball. I think for the coaches listening to this, have someone do that to you. Have your kid or your wife or someone roll you a ball and look at the top and look at the bottom. I think that experience alone, if that doesn’t convince you that there is a visual element of baseball or softball performance that you’ve got to get into, then god help you. Harrison: Well, like I said, the eyes lead the body. If you think about it, your eyes are distracted by motion. They are distracted by light. Your eyes always want to go on to the next thing. They always want to perceive the next thing. Most errors are preceded by visual breakdown. What we believe in is everything begins and ends with what you see and how you see and how you process that information. So even when you grab your door handle, you grab your orange juice, you grab your coffee in the morning, you look at it and then you tend to look away (usually before you ever touch it). 90% of the time you can probably still grab it but there is that 10% chance you miss it and then you go, “How did I miss that?” Again, when we look at the World Series, a lot of breakdowns were visual breakdowns. It wasn’t that the person couldn’t field a ground ball. It wasn’t that the person couldn’t throw from first to home. They visually did not lock in on their target and know what they were doing. They were all over the place. One of the things in hitting that always makes me laugh is all the parents will be yelling, “Watch the ball.” The coach at third base, “Watch the ball.” Well, no. Duh. How many of you players have gotten to the box and said, “Whatever I’m going to do, I’m not going to watch the ball”? You are always trying to do it. But it’s really about how you do it. So to my point, people say, “It’s not that simple as see-ball-hit-ball.” It’s not see-ball-hit-ball. It’s learning how to understand how to see the ball and how to hit the ball and how to have a plan of attack. Again, everything is a visual game. You can’t play with a blindfold on. You can’t drive with your head to the side. You can’t drive with a blindfold. It’s hard to do with a patch as well at a high level. If we can find a way – and that is where [we have the] different tools that we use to train those visual skills. And then from the hardware standpoint, whether it’s a clarity issue, whether it’s a depth perception issue – but then also on the other side is have software to understand how do I get in that visual? How do I slow things down? How do I make that ball look like the moon more consistently? Part of it is controlling where our eyes look. A simple exercise, Brian, is you can do this. As you look at me right now, I want you to spell “California” backwards. What happened to your eyes just now? Cain: Before I even started to spell it I looked to the left. Harrison: You looked to the left and then you looked up and you lost eye control. Your intentions were to keep looking at me but because you got lost in thought, you started to lose control of where your eyes went. So what happens on the field with the infielder? They think, “Don’t make an error, don’t do this,” and their eyes come up and they lose focus of what they were looking at. Cain: Because they’re thinking instead of seeing. Harrison: Correct. Cain: So the quiet mind leads to better thinking, which leads to better physical performance. Harrison: Yeah. Cain: How do you get that? What is a way to train athletes to not be able to think so that they can see better? Is there anything that you give as a routine? Harrison: Yeah, I think routines are very good. I think they depend on each player. I think everyone is a little different on the way they perceive information. We definitely train a visual plan of attack to whatever that sport is. If I have a new sport, whether it’s a football player or tennis player – I had a professional skimboarder, which some of you guys probably don’t know what a skimboarder is. Cain: Yeah, for sure. Harrison: I had a professional skimboarder. He was at the top of his game. He was number two in the world. He wanted to learn, “What can I do to enhance myself to another level? What can I understand visually to do that?” For me, I look at that and say, “What are the visual demands of that athlete and how can we affect that?” Sometimes it’s just making them easily aware of what they’re focusing on. Are they focused on their hands? Are they focused on their vision? Are they focused on the ball? Are they focused on getting hit? And learning how to control that. It’s not easy. I’m not going to say it’s simple, but the more consistent that we can do that, the more we have a plan. When the game gets tough, we know what we need to look for. Cain: That’s awesome. Awesome stuff. For people who want more information, go to www.SlowTheGameDown.com. We are going to change the interview around here and shift away from vision training more into you, Ryan, so people can get to better understand you and your path and your success. Obviously, it’s not every day on the podcast that we get to have someone who is viewed as one of the best in the world at what he does. We have had Olympic athletes, we’ve had Major League Baseball players on here, UFC world champions. For yourself in the field of vision performance training as someone who is at the best in the top of your game, what are the things that you do as a part of your daily routine that keep you consistent and keep you as good as you can be? Harrison: Hmm… good question. I think I’m never satisfied. I think part of my routine is always trying to figure out a better way, always trying to figure out how we can help. I’m not satisfied with being told “no.” I want to find out how we can push the limits. Working with these athletes as well as myself, I want to find out what can we do instead of just accepting what is there. Cain: The question we’ve been asking lately on our podcast here is the best purchase for under $100 that you’ve ever made? The purchase that you made for under $100 that has had the biggest impact on your life? Harrison: The best purchase under $100. That is a tough question, Brian. I’ve got a wife and kids and nothing costs under $100 anymore. Probably the best purchase under $100 … I have no idea. You put me on the spot there. Cain: I thought you were going to say a pair of sunglasses or something but those are probably not under $100. Harrison: Yeah, sunglasses aren’t but those are definitely important too. I mean from the health side of that eye. God, best purchase. That is a challenging question. You didn’t prep me on that one. Cain: It’s on the spot. Best book you’ve ever read or the book that has had the most impact on your life? Harrison: The best book I ever read. Cain: Or the book that’s had the most impact on your life. Harrison: Well, I have to say my dad’s book. The truth is the only reason I say that is over these 16 years I’ve read so much stuff from him that may not be the finished book that’s on there, but it always challenges me to think differently and it pushed me to another level for what we do and not only just accept but (like I said earlier) to challenge. I think it’s kind of funny. You asked a little bit about me. My passion really is a lot of computer stuff. I love being on the computer. I love technology. I love all these other things. But it affects me in a different way. But understanding and watching how my dad works (we’re talking about the book here but at the same time I’ll kind of go off a little bit here), it’s pretty amazing to be able to spend that much time with your father and work with him and see the different successes and be able to prove to him and show him the things that you can take his knowledge to another level. I would be lying if I said it wasn’t challenging at the same time, but to me just some of the readings probably has the most impact obviously on what I do and how I go about things. Cain: As a guy who has worked with your father, is married, kids, on the road a ton doing the consulting and vision performance training, what are some of the keys that you have when you travel as much as you do to stay connected? This is kind of a selfish question that I am asking, probably for my benefit, but I know a lot of the people on the podcast travel a lot too. What are some of the things that you do to stay connected and really grow your family life? Harrison: I think technology has gone beyond our imagination from when I was a kid to now. From my 10-year-old being on e-mail to being able to text with my 13-year -old to being able to be on video chat, I think most of us have been amazed that we can be anywhere and video chat and see things. It is a challenge being on the road and you miss some events. The nice side of that is when I am home, I can spend time and I can help that out. I think it’s not a purchase of under $100 like you asked for but I think the best invention is being able to video chat so easily with family. You can snap pictures and see things. You may not be able to be there but you’re almost there, whereas in the prior years you never had that opportunity. Cain: Yeah. When your dad was traveling (like you are) he’d have to go to a pay phone somewhere. Harrison: Definitely. He still talks about that how he felt bad not being around at certain times. To be honest, I had never felt that way (that he wasn’t around) but now the connection is so much easier. There are times where it’s tough coming home. That is the hard thing, is coming home and reintegrating yourself back into family life. My advice to you is to just let things happen and then ask to be helpful. “Can I help you take the kids to school? Can I help you with this?” I know it’s tough on my wife at times to be able to run the kids around and take care of everything. That is a challenge. But it’s part of the life. And it could be a lot worse. Cain: It can always be worse. Harrison: It can always be worse. Cain: Always be worse. Exactly. Harrison: And on that, I think all the military people who are gone for months, to me that is a very challenging family life to be able to be gone that long. Luckily for me, I don’t think I’ve gone more than two weeks from my family so I am very lucky in that format as well. Cain: Yeah. God bless our military that are gone for six months at a time or more and still able to come home to their families, and how they do that is impressive. Well, Ryan, I appreciate you taking time here, man. The last question for you (which we always ask) is what do you know now you wish you knew then? What do you know now that you wish you knew maybe when you were 20, 25, back in the day? Harrison: I know a lot more now than I did then. I mean there are a lot of things, Brian, as you know. All us 20-year-olds think we know everything. Cain: Oh yeah. Harrison: At my age now there are definitely a lot of things I’d like to take back. I wouldn’t necessarily be a professional baseball player or professional athlete, but I would know how to approach a lot of things differently. I feel that I probably wasted a lot of my time as a youth in my 20s and I wish I could take that time back and be a little bit more productive. Cain: Awesome. Ryan Harrison, www.SlowTheGameDown.com. You can follow him on Twitter @SlowTheGameDown. An e-mail address (if you are sending Ryan an inquiry about having him come and work with your team or speak at your clinic) is [email protected]. Harrison: Correct. Cain: Awesome. Thanks again, man. I appreciate you coming on. You were awesome. Thank you, brother. BC90: RYAN HARRISON – SLOWTHEGAMEDOWN – VISION PERFORMANCE TRAINER Ryan Harrison is a certified Sports Performance Vision Trainer with SlowTheGameDown. He has a degree in Exercise Physiology from University of California at Davis, where he was a kicker for the football team. Since 1998 Ryan has been working with international softball, collegiate and amateur softball teams. Ryan also has been a key consultant to numerous international, professional and collegiate football, baseball & softball teams including USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand women’s national softball teams. He has also worked with various MLB teams including, but not limited to, Philadelphia Phillies, Toronto Blue Jays, San Francisco Giants, Atlanta Braves, Cincinnati Reds, Tampa Bay Devil Rays and Washington Nationals. He has personally trained over 100 Major League roster players on the visual side of the game. Among the Major League players he has trained are Carlos Delgado, Carlos Beltran, Mike Sweeney, Jayson Werth, Delmon Young, Lance Nix, John Baker, Jerry Hairston, Jr., Chris Dickerson, Josh Willingham and Jonny Gomes. Following his work with top professional and amateur athletes, he conceived the idea of training necessary performance skills with digital technology. The SportsEyesite™ Software is a result of his goal to develop training products so that everyone could benefit from this training at a fraction of the cost without the need to go to a specialty clinic. You can connect with Ryan on Twitter @SlowTheGameDown or by e-mail [email protected]. First published in OPTIK February-March 2019EYE-MIND-BODY SPEED  RYAN HARRISON IS THE DIRECTOR OF VISUAL PERFORMANCE AT SLOWTHEGAMEDOWN/ NEURODYNAMIC VISION RYAN HARRISON IS THE DIRECTOR OF VISUAL PERFORMANCE AT SLOWTHEGAMEDOWN/ NEURODYNAMIC VISION Every time you see athletes in any sport do incredible things and wonder, “How did they do that,” it involves an amazing successful coordination of sensorimotor skills. The same is true when athletes struggle and make mistakes—this time there is a breakdown in the sensorimotor skills. The best athletes recognize patterns no one else sees, whether it’s a tennis player tracking the path of a 225 km/h serve, a racecar driver weaving through the bumper- to-bumper grind of the Daytona 500, or a hockey player skating at 32 km/h and backhanding a no-look pass to a teammate across the ice. It is what basketball players see in the open floor, and what star hitters in baseball recognize from the batter’s box. These athletes possess highly developed, highly integrated eye-mind-body speed (EMB Speed). This desirable level of EMB Speed is often influenced by their coordination of a powerful pyramid consisting of several key layers. Think of this as a pyramid of athleticism. The base of the pyramid is the foundation of the athlete. This is the musculoskeletal system. The musculoskeletal system is important to the success of the athlete and dependent on the fitness of an athlete, but without the mind and the visual system it is simply a rock. The middle layer is cognitive. This layer is influenced by mental skills, mental toughness and mindfulness. The athlete must have the desire to accomplish the task. The peak of the pyramid is the sensory layer. This is the input of information from our environment that tells us how to perform. In most sports this sensory input begins with the visual system. This is the input of information from our environment that tells us how to perform. In most sports this sensory input begins with the visual system. So how do athletes control this desirable sensorimotor interaction? Those that possess great EMB Speed and control see their game in large chunks, and it all appears in slow motion. These athletes see order in chaos. They can see slight information and process at a higher rate. More than foot speed or strength or nerve, phenomenal athletic performances require the kind of neural speed and control that blurs the line between thought and action. Those without these skills see the game like a blur, miss important visual cues and are often late to react as they make more mistakes. Put simply, an athlete with great EMB Speed and Control sees the game at a higher level and performs actions without delay or thought. This is what we’re seeing when we can’t believe our eyes. Our approach to performance vision involves finding the most practical, accessible and affordable way to integrate into athletic action. Evaluation and training the eyes to access the visual centers in the brain has clearly demonstrated an effective way to increase the speed and control the body to act and react. EMB Speed is not about visual acuity but can be affected by poor visual acuity. EMB Speed is more about the ability to discern and process the most import visual cues to an action and react with accuracy without much thought. When evaluating an athlete for EMB Speed we will evaluate clarity, ocular motor control, post-concussion syndrome, balance, and speed of processing. When training EMB Speed and Control we focus on decision making, moment integration, speed of processing and fine focus acquisition. Today’s competitive environment requires precision in data input and processing for a performance edge that separates the good from the great. EMB is another neurodynamic vision tool that offers an effective way to combine physical movement with sensory-cognitive decision-making to unleash maximum athletic potential. Bill Harrison, OD, is a sports vision specialist and author with 45 years of experience and the founder of SlowTheGameDown, which provides performance vision training for athletes. The clients he has worked with include the Toronto Blue Jays and San Francisco Giants.

Reacting to a fastball coming in at 100 miles per hour is one of the most difficult feats in professional sports. A hitter has a mere four-tenths of a second to react to a pitch. When a baseball travels that quickly, the margin for error is razor-thin. A batter can have all the power in the world, but if their timing is off by a fraction of a second, that’s the difference between fouling off a pitch and parking a ball in the stands. There are many muscle groups working in unison for a hitter, but no muscle group is more important than a hitter’s eyes. Although those ocular muscles can’t be “bulked up” in a traditional sense, there are ways for a hitter to train their eyes to see more clearly at the plate. That’s the mission of Bill and Ryan Harrison: the father and son duo behind the esteemed vision training company Slow the Game Down. They’ve worked with everyone from former MVP George Brett to the 2015 American League East Champion Toronto Blue Jays. Ryan is a certified sports performance vision trainer who helps pro and amateur athletes by using visual and mental drills to see better, which can translate to improved results on the field. He worked closely with the Blue Jays organization from 2011 to 2015, helping players like Jose Bautista, Kevin Pillar and Ryan Goins train their eyes. It sounds simple, but with a ball barreling towards them at speeds of 100 miles per hour or more, a hitter has to execute a perfect set of steps to square up that pitch. Harrison explains how he helps train baseball players to “slow the game down” and give themselves a fighting chance at the plate. We evaluate how the eyes and muscles work and how the eyes and the brain interact. The brain uses vision based on past experiences. The more pitches someone sees, the more ability they know how to react to what they see. When it comes to the fastball, you can get away with some bad visual habits. That’s why you can get a guy who can train off a pitching machine and hit a fastball all day long, but when it comes to the game, it’s a lot more challenging to react. They have to have a heightened visual awareness to perform efficiently. The best hitters on the planet are capable of inhuman things on the plate, but it’s physically impossible for the human eyes to track a fastball coming towards them at 100MPH. This is where a hitter uses repetition to fill in the blanks so it becomes second nature. They use thousands of pitches’ worth of experience to predict where the ball will go. When most people think of “vision”, their mind goes towards the typical “better or worse” lens test performed by an optometrist. Static vision tests barely scratch the surface for athletes like baseball players who rely so heavily on their vision for reaction time. Harrison says that all MLB teams perform a standard vision test on their players, but not all clubs administer an advanced baseball vision test. The basic vision test is black and white. It’s static, the person doesn’t move and it’s just basic standard clarity. Where baseball vision is more about contrast sensitivity, the ability to see under movement and also how the brain uses the eyes for depth and where they see the ball. The basic vision test is for basic visual skills like driving and walking the street. A lot of players will say ‘I’ve already had my eyes checked’, but they’ve never really had a full-in depth baseball vision test. Testing vision is standard practice for most professional teams, but not all clubs go beyond the rudimentary eye exam. It’s modern practice for teams to employ their own internal high performance department, which may or may not delve into vision training. If vision training isn’t offered at the professional level, MLB players often seek out baseball vision training programs on their own accord. During the offseason, Randal Grichuk enrolled in vision training in an attempt to improve his plate recognition. *** Baseball is so much about timing, but it’s also about getting the eyes and the brain to work in unison. There’s a distinct difference between hearing and understanding, just as there’s a difference between seeing something and processing the information your eyes have seen. Players with good visual habits are able to pick up the spin on a baseball and determine within a fraction of a second whether or not they’re going to swing at the ball. Just as much as pitchers study hitters, hitters scout pitchers to pick up release points and arm slots to give themselves a fighting chance at the plate. Bad visual habits don’t just affect professional athletes, it can impact everyday people. Harrison likens it reading a book or an article, but being distracted or not fully immersed in reading the words. Afterwards, the mind can’t recall what your eyes just saw. That can happen to pro hitters if they get in the box and they’re thinking too much or trying to do too much; they never recognize what their eyes are aimed at. If you don’t see the ball early and you don’t track it because you’re lost in thought or your eyes aren’t in the right spot, you shorten that distance from the mound to home plate. By not picking up the ball or looking in the wrong location, in essence, the hitter does what Harrison suggests; it gives the pitcher an advantage start by shortening the distance to home plate. Traditional strength training focuses on specific muscles and the results are measurable. The eyes are a different story; they involve a specific set of muscles, but how does one exactly train them? Harrison explains: There are 14 muscles of the eyes, 12 of which are involved in tracking a ball. And those muscles are very strong – they can’t get any stronger, but they could be more fluid and the neurons could fire a lot better. Under stress, those muscles tense up and the eyes don’t track as well and everything starts to look the same speed. Back in January, Hall of Fame baseball writer Peter Gammons mentioned Jose Bautista by name on MLB Network, saying, “his vision was really bad”. It stemmed an interesting conversation about Bautista’s struggles and whether they were vision-related. Traditionally, he was one of baseball’s best pitch trackers, sporting MLB’s second-best walk rate (15.5%) from 2010 to 2017. Only Joey Votto had a better walk rate (17.5%) during that eight-year span. How could a baseball player’s eyesight to deteriorate that quickly? As with most things, it isn’t a simple black and white issue. Without working with Bautista closely, Harrison couldn’t provide a thorough diagnosis, but he has some clues about why he thinks the former Blue Jays slugger struggled in 2017. He’s trying to force things a lot more, instead of allowing his vision to work for him. I think there is some clarity issues Bautista has as well, which can create some reaction timing issues. It’s like your car being out of alignment. It still works, it’s just not working at optimal ability. Your eyes are working, but they’re just not working at an efficient, easy level. Those issues aren’t big enough issues to prevent someone from driving, but it prevents them from seeing that contrast, spin and the change of and direction of the baseball more clearly. It’s almost like he’s trying to play with a backpack of weights on him. He’s an athlete, so he’s going to fight through it, and he’s experienced, and there are sometimes he’s going to be smarter than his eyes and get lucky. Harrison recalls working with another former Blue Jays heavyweight with vision issues: Carlos Delgado. Upon a recommendation by his teammate Carlos Beltran, Delgado and Harrison worked together on some exercises while the Mets were on the road in California prior to the 2008 All-Star break. Delgado’s second-half numbers increased dramatically, as he went from a .784 OPS in the first half of the 2008 season to a .991 OPS post All-Star break. Harrison remembers the advice he gave Delgado; telling the Mets’ first baseman he had essentially blocked his eyes from working for him. It’s not that you’re old. The problem is, you’re not giving yourself enough visual time to make the proper reaction. Vision training is slowly gaining traction around Major League Baseball and many clubs see this avenue as a valuable tool. Harrison notes that some clubs have adopted his teachings related to baseball vision, but others have yet to realize the tangible benefits of a program like “Slow the Game Down”. It’s a lot easier to work on strength and mechanics because you can see the benefits, the exterior side of it. With visual, some people think you either see or you don’t see. In pro ball, even though we’ve been doing this for a very long time, it’s still slow to adopt. As word gets around baseball and other professional sports, visual training is gaining prominence as an important resource. In the past, evaluators looked for fluid swings for hitters, but Harrison says good visual habits are paramount at the plate. You can have the most beautiful swing, but if you don’t see the ball, it doesn’t matter. Ian Hunter Ian has been writing about the Toronto Blue Jays since 2007. He enjoyed the tail-end of the Roy Halladay era and vividly remembers the Alex Rodriguez "mine" incident. He'll also retell the story of Game 5 of the 2015 ALDS to his kids for the next 20 years.  Your decisions this fall are critical as they impact your upcoming season. One decision is what you are doing or not doing regarding the training of the visual side of the game. The visual side of the game includes early, accurate recognition of the ball’s actions, tracking the ball, staying visually focused at contact or until it is secured in the glove. One consideration is that either poor visual habits or poor visual skills result and reacting to the ball later. On the other hand, high level visual skills and habits result in seeing and reacting to the ball sooner. There is power in small wins and slow gains. Consider searching for 1 percent visual improvements in the visual side of the game in all your players. Improving by just 1 percent isn’t notable. Sometimes improving by just 1 percent isn’t even noticeable. But it can be just as meaningful, especially in the long run. It’s the sum of many small reactions — a 1 percent improvements here and there — that eventually leads to success. As a cautionary consideration, continuous, small, slower reactions work the same way in reverse. For example, if your defensive players read the hit ball 1 percent later, they are going to be 1 percent slower in their reactions. The same is true with your baserunners. Hitters that see the ball later are going to be 1 percent slower in their reactions. Initially, there may be little observable difference between making a choice that is 1 percent better or 1 percent worse. But as time goes on, these small improvements or declines compound and you suddenly find a very big gap between the players who make slightly faster reactions and those who don’t. Therefore, small choices don’t make much of a difference at the time, but add up over the long-term. During the upcoming seasons, if you find your players stuck with bad habits or poor results, it’s usually not because something happened overnight. It’s the sum of many small choices — a 1 percent decline here and there — that eventually leads to a problem. Almost every habit that your plyers have — good or bad — is the result of many small decisions made over time. The most common decision is to demean dismiss or put down the importance of the visual side of the game. Let that be your opponents. Make the decision to get your players visually better, visually quicker, and to react faster. Success is a few simple disciplines, practiced every day. In contrast, failure is simply a few errors in judgment, typically visual, repeated every day. It’s so easy to overestimate the necessity of one defining major change or accomplishment and underestimate the value of making continuous, better choices daily. The truth is that most of the significant things in life are the sum of all the moments when we chose to do things 1 percent better or 1 percent worse. |

Company |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2024. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed